What was Gilmans most likely reason for sending a copy of her story to her former physician?

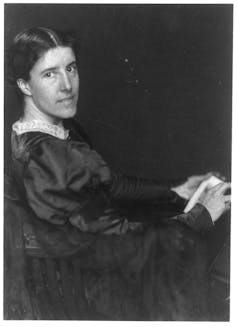

"These nervous troubles are dreadfully depressing", wrote Charlotte Perkins Gilman in her brusque story, The Yellow Wallpaper. Though later gaining recognition equally a journalist and social critic rather than an author of fiction, Gilman is best known for this brief and extraordinary piece of writing published in 1892.

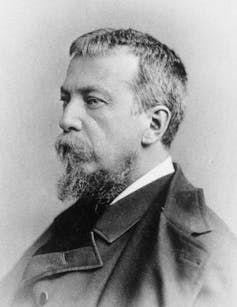

The Yellowish Wallpaper enlightens the reader on women'south health, motherhood, mental breakup and its handling, too equally feminism and gender relations in late 19th-century America. Though many details are inverse, the story is semi-autobiographical, cartoon on Gilman's own health crisis and particularly her fraught human relationship with Dr Silas Weir Mitchell – who carved a reputation for treating nervous exhaustion post-obit his experiences as a Civil War doctor – and who was brought in to treat her in 1886. In Gilman's own words, he drove her to "mental agony" before she rejected his treatment and began once again to write.

Gilman's short story is a straightforward 1. The narrator is brought by her physician married man to a summer retreat in the countryside to recover from her "temporary nervous depression – a slight hysterical tendency". There she is to balance, take tonics, air and exercise – and admittedly forbidden to engage in intellectual work until well once more. The house is "queer", long abandoned and isolated. The room her husband selects as their bedchamber, though large, airy and brilliant, is barred at the window and furnished with a bed that is bolted to the flooring. The wallpaper is torn, the floor scratched and gouged. Perhaps, the narrator muses, it had once been a plant nursery or playroom.

It is the room's wallpaper, a "repellant" and "smouldering unclean xanthous", with "sprawling flamboyant patterns committing every artistic sin" that forms the centrepiece of the story. The narrator spends much of her days being cared for – and oft left lone – in this room, reading, attempting to write (though the subterfuge this involved leaves her weary, she noted) and, increasingly, watching the wallpaper, equally information technology starts to take on a life of its own.

Nervous exhaustion

The story highlights the plight of many women during the 19th century. All women were seen by physicians as susceptible to sick health and mental breakdown by reason of their biological weakness and reproductive cycles. And those who were artistic and aggressive were deemed even more at chance.

The protagonist of the story might take been suffering from puerperal insanity, a astringent form of mental illness labelled in the early 19th century and claimed by doctors to be triggered by the mental and physical strain of giving nascence. The status captured the involvement of both psychiatrists and obstetricians, and its handling involved quietening the nervous system and restoring the strength of the patient. In her autobiography, published in 1935, Gilman wrote of the "dragging weariness … accented incapacity. Absolute misery" post-obit the nascence of her daughter that led her to consult Dr Mitchell.

The story can likewise be seen as a rich account of neurasthenia or nervous exhaustion, a disorder first defined past Mitchell in his book Wear and Tear, or Hints for the Overworked in 1871. Neurasthenia took hold in modernising America in the closing decades of the 19th century, as incessant work was said to ruin the mental health of its citizens. Women were reported to be putting themselves at hazard of nervous collapse with their eagerness to take on roles unsuited to their gender, including higher teaching or political activities. "Urban center-bred" women, Mitchell concluded, might exist poorly equipped to fulfil the natural functions of maternity.

Gilman was treated with the "rest cure", devised past Mitchell, as is the protagonist of the story; similar an infant, she was dosed, fed at regular intervals and above all ordered to residual. Mitchell instructed Gilman to live as domestic a life as possible "and never touch on pen, brush or pencil as long as you live".

Escape from the wallpaper

Information technology is the wallpaper that dwells increasingly on the narrator's mind with its "vicious influence". Behind it, dim shapes get clearer by the day, sometimes of many women, sometimes ane, stooping downwards and creeping near backside the pattern. At the finish of the story the narrator takes the opportunity of her hubby'due south absence to lock the door and tear away the wallpaper, the women now creeping outside in the garden. "I wonder if they all come out of that wallpaper every bit I did?" she asks. Her husband, on opening the door, collapses equally the narrator declares:

I've got out at last … and you tin't put me back. Now why should that human being have fainted? But he did, and right across my path by the wall, so that I had to creep over him every fourth dimension!

Was her "escape" her salvation or had she finally lost her mind? Readers are left to reach their own conclusions.

The Yellow Wallpaper illuminates the challenges of being a adult female of appetite in the belatedly 19th century. While all women were seen vulnerable, those who expressed political ambition (suffrage reformers), or who took on male person roles and challenged female wearing apparel codes (New Women), or who sought higher education or creative lives – or even read too much fiction – could exist defendant of flouting female conventions and placing themselves at risk of mental illness. Mitchell, largely through his handling of Gilman and her afterwards description of this, gained a notorious reputation, and he may well take misdiagnosed her or believed that her intellectual pursuits were too introspective.

Yet historical scholarship has also suggested that some well-to-do and educated women might besides accept helped shape their ain diagnoses or used their illness to avoid domestic duties that they found unpleasant or taxing. Not all doctors condemned women for their appetite – many advocated more rounded lives embracing intellectual and physical pursuits alongside domestic roles. Other patients treated by Mitchell, including the critic and historian Amelia Gere Bricklayer and writer Sarah Butler Wister, tailored their treatments to suit their lifestyles, with Mitchell encouraging their intellectual and creative pursuits.

For Gilman, her divorce proceedings, rare enough at the time to be appear as a "scandal" in various American newspapers, began in the aforementioned twelvemonth every bit The Yellow Wallpaper was published, and she became increasingly active in the women's movement. Writing years subsequently virtually the short story, Gilman described how information technology was written to celebrate her narrow escape from utter mental ruin. A copy was sent to Mitchell but did not receive a response.

thompsontherameatelf.blogspot.com

Source: https://theconversation.com/the-yellow-wallpaper-a-19th-century-short-story-of-nervous-exhaustion-and-the-perils-of-womens-rest-cures-92302

0 Response to "What was Gilmans most likely reason for sending a copy of her story to her former physician?"

Post a Comment